THE GOLD FAMILY LEGACY IN DANCE EDUCATION

The Gold family has decades of history in teaching, performing and coaching. This history guides the mission of Rhee Gold's DanceLife and helps to pass on the importance of quality dance education to the next generation.

A Stubborn Passion

by Rhee Gold

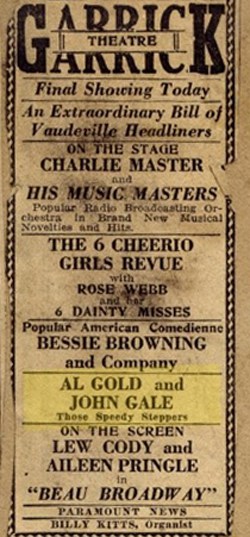

Around age 15, my father went on the road to work during the tail end of the vaudeville era. Family legend has it that he had lost his cool with a school teacher, kicked him in the shin and took off from school, never to return. Born in 1909, my father, Al Gold, was a traveling vaudevillian.

Looking through family photo albums, I have pictures of him with dance partners dating back to 1924, but I assume he had begun to dance before then. In those days you weren’t just a dancer, you did it all. My father was a comic, he performed musical skits, and was a master of ceremonies for burlesque shows, plus he was a tap dancer and could do a mean old soft shoe. He shared the stage with celebrities such as Milton Berle, George Burns, and Peg-Leg Bates. When I was a kid, I loved the story that he had even performed with the Three Stooges! Life on the vaudeville stages was exciting, always moving from one city to the next by car or train.

My father continued performing through the end of the vaudeville era. Meanwhile, in a small farming town in Arkansas, my mother, Sherry Bethel was born in 1935, twenty-six years after my father. By 1942, World War II was in full swing. My grandparents had moved the family to Michigan (to work in the factories manufacturing airplanes and weapons), and my mother was diagnosed with curvature of the spine. Her doctor recommended that she take ballet lessons—it was the beginning of her lifelong passion for the art of dance.

Trained in all forms of dance, including successful passage of all grades of the Cecchetti ballet syllabi, my mother became a talented and well-balanced dancer. An old classmate of hers recently told me of a time when their dance teacher asked the entire class to sit in a circle around my mother to watch her do more than one-hundred fouette turns! By age twelve she was performing as a tap dancer and acrobat. One stint was tap dancing on the RKO Radio broadcasts out of Chicago.

At 17, my mother married, but her husband was soon off to the Korean War. My mother was pregnant with my older brother Tony when her husband was deployed, but she was not one to sit and wait. She was ambitious for her family to get ahead; she bought a house and started a school. Three years passed before her husband returned from Korea. During that time she had learned to be self-sufficient, managing her own home with a toddler in tow, creating a flourishing business, and paying her own bills. She was confident of her well-earned self-esteem.

on ABC Radio 1947 (age 12)

Her husband wanted a dependent, stay-at-home wife in the June Cleaver image that he saw on the new television set. He believed he should be making the living, insisting that my mother stop working and give up her school. She was already three years ahead of him as a strong, independent, member of the community. In three months, they were separated, and soon divorced. Now she decided to return to her dream of performing. Closing her school, she packed Tony off to stay with my grandparents, changed her name to Sherry Michaels, and she, too, was on the road.

Like my father, my mother did it all. Some newspaper reviews refer to her as the “fast-tapping redhead,” and a “magnificent contortionist.” Performing in night clubs and theaters, she shared the stage with entertainers such as Bobby Darin, Norm Crosby, and Louis Armstrong. She was crisscrossing the country, performing night after night, and loving every minute of it.

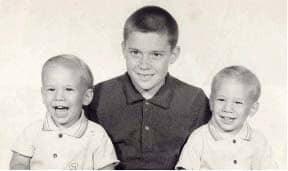

By the late 1950s my father-to-be had become a Boston theatrical agent, booking acts all over the New England area, which was a booming business at the time. Boston attracted my mother as a home base because there was so much work there. Al Gold became her agent. Before long she was working in his office during the day while she performed at night. Despite a twenty-six year age difference, they fell in love, married in 1960, and nine months later, my twin brother Rennie and I were born.

My mother continued to perform on a limited basis for several more years. I remember watching her on stage knowing that this was what I was going to be doing some day. By this time my mother imagined a different kind of life—thinking she was ready to become that housewife she couldn’t be years before. The catch to her plan was this passion that continued to burn inside of her—you know the one—the need to dance that runs in your veins and you can’t get it out of your system, no matter how hard you try. At the same time, neighbors started asking her to teach dance to their children. In 1964, the Gold School of Dance was founded in the basement of our home, with three poles, a tiled floor, and (maybe) six-and-a-half-foot ceilings. The first students registered were Rennie and me.

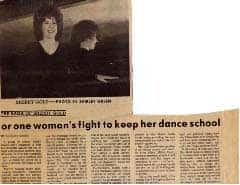

The school took off, growing to more than two hundred students dancing through each week. For years, our house was always under construction because my mother was adding on to her basement school. But the same neighbors who had encouraged her to teach their children began trying to have her business shut down. It wasn’t just the traffic and parking and music that were at issue. The community’s zoning laws had changed, but the all-male council had grandfathered in all the male-owned businesses around. Apparently it was okay for women to be elementary schoolteachers or nurses, but not successful, competitive businesswomen. My mother fought them for years.

Once, a police officer came to the house with a cease-and-desist order. He marched down the stairs to find my mother sitting on the floor with a “baby class.” She said, “You’re going to have to drag me out of here in front of all these babies if you want me to stop teaching.” He didn’t. Parents from the school, encouraged by my mother’s stubborn bravery, marched on town hall with picket signs. The story of Sherry Gold’s fight to keep her dance school became front-page news and her business flourished from the publicity. The situation had a major impact on me. Watching my mother fight for her livelihood was a huge inspiration—making me understand that when we’re under fire, we all have to fight for what we believe in.

Herald "one woman's fight to keep her

dance studio (1972)

After three years of defying cease-and-desist orders, my mother secured a commercial building and moved her school there. Despite her struggles to keep her dance school, she always continued to educate herself and had built a reputation as one of the finest teachers in New England. Eventually, students and teachers were traveling from as far away as Rhode Island and Maine to take classes in her Boston-area school.

Although the golden age of live show business had come to an end, my father continued to work as a theatrical agent. Rennie and I traveled to work with him every Saturday, where he was one of many “old time” agents in his office building. Many of them were the George Burns cigar-smoking types from the days of vaudeville. They reminisced to us about the good old days. From them we learned what true entertainment was about; they told us that entertaining was about winning over the audience and that it had nothing to do with how many pirouettes you could do. I look back at those Saturdays, hanging out at my father’s office, with great fondness. We had the chance to remember with those who had experienced an era of entertainment and show business that my generation would never witness, yet we had the chance to hear about it from those who had known it.

Soon my mom was a respected master teacher, working for every major dance organization in the country. As Rennie and I grew older she took us with her to assist; we worked with some of the greats, including Gus Giordano, Luigi, David Howard, Beverly Fletcher, Fred Knecht, Joseph Giacobbe, Lee Theodore, and so many others. Each of them was a tremendous influence on who we are today. I remember thinking that someday I was going to be just like them. By the time Rennie and I were 15, we were teaching our own classes at conventions. We were flying to three different cities on the same weekend. Other times we traveled as the Gold Family, all three of us at the same convention. I loved that.

With the performing bug still in her, and her desire to be sure Rennie and I had professional performing experience, my mother started a dance company when we were 15. The Sherry Gold Dancers traveled all over the Northeast and my father became our agent. We booked everything from railroad conventions to weekly appearances on the television show, Stage Door Disco. Our parents instilled the concept that we were dancing to entertain, to impress the agents, club owners, and of course, the audience. Although my mother’s classes were all about strong technique, my parents often said, “The audience has no idea about good technique—they want to be entertained!”

We started our first competition as a fund-raising event to pay for new costumes for the Sherry Gold Dancers’ appearances in Las Vegas. By the time our performing group broke up, the competition business had grown too big to abandon. First as Gold Family Presents, then as American Dance Spectrum, we added cities in the Northeast to our schedule. My brother Tony and I borrowed money against a house we owned jointly, and I expanded the competition to be a national event. We were the first to be an adjudicated competition where every competitor and teacher got feedback on their performances. We were also the first to go beyond awarding medals; we always hired one independent judge to look for “special qualities,” so dancers who might not win first, second, or third, were encouraged to develop their art and skills. As American Dance Awards, we became one of the largest and most successful competitions in North America.

Meanwhile, my mother had opened a second school and Rennie and I opened our own school in Boston and continued guest teaching somewhere almost every weekend. As Dance Theater of Boston and then as Gold Studio III, we went through all the pains of starting a new business, including losing leases on our sites, sharing studios, and trying to build a steadily returning paying clientele. Some nights we slept on the floor of the studio because we hadn’t taken in enough cash that day to get the car out of the parking lot. After about three years, Rennie went back on the road as a dancer and choreographer, and then later settled in Florida at Disneyworld. I closed the school and worked from a garage selling routines to dance teachers in the competition’s off-season.

In the early 1980s my father suffered a stroke and was confined to a nursing home for the remainder of his life. Even then he couldn’t let go of the art he loved. Once the head nurse called to insist that my father could not run a business from his hospital bed. It seems he was still booking acts from the nursing home. In 1986, he passed away after suffering many more strokes.

By the early ’90s, my mother’s students were moving on to professional careers throughout the entertainment industry, and many had become respected teachers. She had added a second floor to her studio, which now boasted three classrooms and close to 10,000 square feet of space. Her hard work had at last paid off. Unfortunately, in late 1993 she was diagnosed with cancer of the lungs. My brother, Rennie, my brother, Tony and his wife, Kim, and their children, all moved to my house to be near enough to care for her. She fought for life as she had for her school, but it wasn’t enough. In August of 1994 she lost her final battle at age 59.

Rennie returned to Florida and Disneyworld, Tony and his family moved back to their home, and I found myself as the owner-director of the Sherry Gold Dance Studio. Because her school was scheduled to open its thirty-first season in just two weeks, the period following my mother’s death was intensely emotional. The “Gold Family,” as we had known it, would never be the same, and my mother’s students were devastated by her loss. I was handling registration, fitting young dancers for shoes, having faculty meetings, all the while wondering how I was going to keep the school running. Moving my competition company offices into the studio building, I worked around the clock to maintain both businesses. I also had been elected national president of Dance Masters of America. I was approaching burnout, yet I didn’t want to give up the school—it had inspired so many, but I knew something had to change.

Timing was everything—Rennie was leaving Disneyworld and thinking he might like to run the school. I jumped at the opportunity to keep the business in the family. I sold the studio to him and moved my offices to a separate location. During 2004, under Rennie’s leadership, the Sherry Gold Dance Studio celebrated its fortieth anniversary with more than 400 students dancing through every week. Our family school had come a long way from the days in the basement. I’m proud of Rennie’s success and that he keeps the Sherry Gold legacy alive with excellent choreography and dance training and experience for students.

With a new sense of normalcy in my life, I continued to produce dance competitions and in the summer of 1996 I was sworn in as the youngest president in the history of DMA. I felt strongly that there was a need for dance educators to come together. There was a buzz again in the field concerning a movement to require certification and regulation of dance teachers. Although I support the concept of good teaching, proper training, and continuing education, I know that dance is an always-evolving art with many techniques and differing audiences. Bureaucratic restrictions on what we could teach or how we had to conduct our classrooms could stifle the evolution. There was also talk of eliminating all basement-based schools that were often referred to as “Dolly-Dinkle” dance studios. Having learned my skills in the basement of our home, I was especially sensitive to that issue, feeling that our school and many other small businesses might never have existed under these proposed guidelines.

There were other organization leaders who felt the same way that I did. With the support of Dance Masters of America, I initiated the first UNITY meeting in 1996. It was the first time in living memory that the leaders of major dance organizations came together in the same room to talk about the issues that affected their memberships. It was a day that I’ll never forget. UNITY continues to meet regularly, bringing numerous representatives together to communicate and discuss the state of the field.

By 2002, I—and a large staff—was running close to fifty dance competitions across the United States and Canada. Having launched the company that was by now called American Dance Awards at age seventeen, I counted that I had been at it for twenty-four years. I had watched the field change and grow, and it was time for me to get off of what I referred to as a speeding train. In August of that year, Gloria Jean Cuming took over the reigns as the owner-director of ADA.

In the fall of that year, I launched a new company that would produce Project Motivate, business and motivational seminars and materials for teachers and school owners. It was my way of taking my parents’ influence and my own life experiences to another plane. I wanted to reinforce the positive aspects of dance education, to help educators meet the challenges of small businesses, to re-invigorate and inspire the teachers so they could pass on their love of dance.

For six years I had been working on a book for dance teachers, but could never get the time to get it published. In the summer of 2004, I published “The Complete Guide to Teaching Dance”. The book is meant to be just one more tool in the kit of successful dance educators.

After serving as an education columnist for Dance Magazine and Dancer, I jumped into the publishing business, launching Dance Studio Life magazine six years I had been working on a book for dance teachers, but could never get the time to get it published. In the summer of 2004, I published “The Complete Guide to Teaching Dance”. The book is meant to be just one more tool in the kit of successful dance educators.

As I look back at the more than 80 years of the Gold family legacy, I count strength and stubbornness to stand for our ideals and philosophies as our heritage, of a passion to move and create new ways to achieve, of a commitment to lifelong learning and high quality dance education. Most of all, it is the willingness to empower and validate those who dance and those who pass along their love of this art.